Slave Laws in the Old Testament

A comparison of Exodus 21, Deuteronomy 15, and Leviticus 25

Biblical law concerning slaves was similar to that of other Near Eastern nations. Slave labor was used for domestic service and thus made for a close relationship between the master and the servant. In spite of the legal status of slaves, their position was closer to that of family than to that of common chattel. 1

Some of the slaves in Israel were captives of war and were considered to have been acquired by the person who had spared their lives (Numbers 31:26; Deuteronomy 20:10-14; 21:10). Foreign slaves could also be acquired by purchase (Exodus 12:44; Leviticus 22:11; 25:44-45). Hebrew children were enslaved by sale if their fathers saw no other way of meeting their obligations (2 Kings 4:1; Nehemiah 5:5; Proverbs 22:7; Isaiah 50:1; Amos 2:6;l 8:6). Poor people might be driven to sell themselves into serfdom (Leviticus 25:39) in order to pay their debts, or to change from temporary to permanent slavery in order to retain their security (Exodus 21:2-6; Deuteronomy 15:16-17).

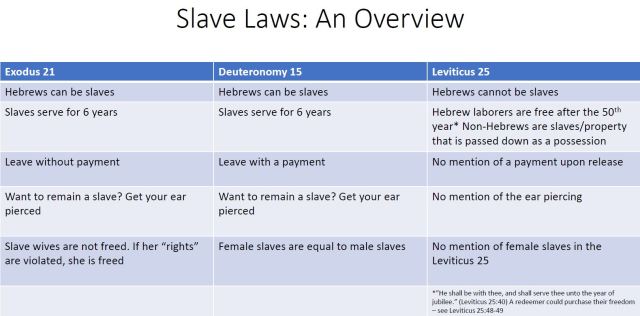

The slave laws in the Old Testament are an excellent source of information to see just how the different authors of these texts are more easily seen and understood by the modern reader. If the first five books of the Bible were all written by one single author, we would see something very different than what we see in these books of the Bible. The idea that the first five books of Moses, or the Pentateuch had several authors is known as the Documentary Hypothesis. The Pentateuch has three sources of slave law: the Elohist (Exodus 21:1-11), the Deuteronomist (Deuteronomy 15:12-18), and the Priestly (Leviticus 25:39-55).

The dating of these laws

From the scholarly perspective, the earliest of these three slave laws was Exodus 21, part of what is called the Covenant Code (Exodus 21:1-23:19) in scholarly circles, written by the Elohist author. (The Elohist textualized his narratives sometime between the division of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms in 921 and the 722 B.C. fall of the Northern kingdom)2 Many years later the Deuteronomist (640-609 B.C.) will react to these laws and add to them, followed by the Priestly author as found in Leviticus 25. 3

From the scholarly perspective, the earliest of these three slave laws was Exodus 21, part of what is called the Covenant Code (Exodus 21:1-23:19) in scholarly circles, written by the Elohist author. (The Elohist textualized his narratives sometime between the division of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms in 921 and the 722 B.C. fall of the Northern kingdom)2 Many years later the Deuteronomist (640-609 B.C.) will react to these laws and add to them, followed by the Priestly author as found in Leviticus 25. 3

The Elohist slave law as found in Exodus 21

2 If thou buy an Hebrew servant (ebed, עבד slave), six years he shall serve: and in the seventh he shall go out free for nothing. 3 If he came in by himself, he shall go out by himself: if he were married, then his wife shall go out with him. 4 If his master have given him a wife, and she have born him sons or daughters; the wife and her children shall be her master’s, and he shall go out by himself. 5 And if the servant shall plainly say, I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free: 6 Then his master shall bring him unto the judges; he shall also bring him to the door, or unto the door post; and his master shall bore his cear through with an awl; and he shall serve him for ever. 7 And if a man sell his daughter to be a maidservant, she shall not go out as the menservants do. 8 If she please not her master, who hath betrothed her to himself, then shall he let her be redeemed: to sell her unto a strange nation he shall have no power, seeing he hath dealt deceitfully with her. 9 And if he have betrothed her unto his son, he shall deal with her after the manner of daughters. 10 If he take him another wife; her food, her raiment, and her duty of marriage, shall he not diminish. 11 And if he do not these three unto her, then shall she go out free without money.

The law for male slaves has three main parts:

- A Hebrew slave serves for 6 years after which he must be freed. (Exodus 21:2).

- The slave leaves without payment – with a wife if he had one before he came, but not with a slave wife or slave children (Exodus 21:2-4).

- If the slave volunteers to stay with his master, the master then pierces his ear at the doorpost and he becomes a slave for life (Exodus 21:5-6).

This law about male slaves is followed by a second law that concerns female slaves that reverses the structure of the male slave law:

- A man never need free his slave-wife (Exodus 21:7).

- If he doesn’t want her he can let her be redeemed (but he may not sell her), or he may marry her to his son, and if he marries someone else he must continue to support her (Exodus 21:8-10).

- If he violates her rights, he must free her without any payment (Exodus 21:11).

The Deuteronomist as found in Deuteronomy 15

The second of the three slave laws is found in the Deuteronomic Law Code. This code is an old, independent document that was used by the Deuteronomistic historian to comprise chapters 12-26 of the book of Deuteronomy. The slave law in Deuteronomy 15 comes right after the discussion of shemitah, the requirement to forgive debts every seven years, known as the sabbath year (shmita Hebrew: שמיטה, literally “release”) also called the sabbatical year or shevi’it ( שביעית, literally “seventh”) and is the seventh year of the seven-year agricultural cycle mandated by the Torah for the Land of Israel the requirement to offer poor people loans:

12 And if thy brother, an Hebrew man, or an Hebrew woman, be sold unto thee, and serve thee six years; then in the seventh year thou shalt let him go free from thee. 13 And when thou sendest him out free from thee, thou shalt not let him go away empty: 14 Thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith the Lord thy God hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him. 15 And thou shalt remember that thou wast a bondman in the land of Egypt, and the Lord thy God redeemed thee: therefore I command thee this thing to day. 16 And it shall be, if he say unto thee, I will not go away from thee; because he loveth thee and thine house, because he is well with thee; 17 Then thou shalt take an awl, and thrust it through his ear unto the door, and he shall be thy servant for ever. And also unto thy maidservant thou shalt do likewise. 18 It shall not seem hard unto thee, when thou sendest him away free from thee; for he hath been worth a double hired servant to thee, in serving thee six years: and the Lord thy God shall bless thee in all that thou doest.

The Deuteronomist’s slave law includes:

1. The liberation of the slave in the seventh year (Deuteronomy 15:12).

2. The freed slave is to be paid (Deuteronomy 15:13-15).

3. If the slave desires to stay in the master’s house, he is marked with the awl (Deuteronomy 15:17).

4. Female slaves are treated as male slaves in the Deuteronomistic source (Deuteronomy 15:17b)

The Common Elements of Exodus and Deuteronomy

The arrangement of this legislation in Deuteronomy is more complicated than Exodus, but the two laws share a similar structure.

The linguistic similarities consist of:

-

-

-

-

- He is a Hebrew

- Work for six years, free on the seventh

- Going free

- Loving the master

- The awl

- The ritual of piercing at the door

-

-

-

Differences between Exodus and Deuteronomy

Despite this general resemblance, many of the details of these two laws are dissimilar even in this related section. In Exodus, he is called a “slave” (ebed עבד). In Deuteronomy, he is referred to as “your brother” (‘ach אָח) In Exodus, in addition to his master, he loves his slave-wife and children, while in Deuteronomy, the slave loves his master’s house and the situation, something that is “good” for him.

Paying the liberated slave when released in Deuteronomy

According to Exodus, the slave leaves without payment when he is released from bondage. According to Deuteronomy, the freed man must be supplied with animals from the flock, grain “from the floor,” and wine.

The text goes on to justify this requirement with a number of points: That which you have is a blessing from God; you must remember that you were once slaves in Egypt and God freed you; the slave has worked for you just as a wage-earning worker does, so he deserves payment.

Female Slaves

The textual approach of the female slaves varies clearly between these two texts.

In Exodus, a daughter of an Israelite male becomes a slave-wife and is never freed unless mistreated. Other women, probably non-Israelites or not under the protection of an Israelite man, are slaves for life and used to produce slaves for the next generation.

In Deuteronomy, the Hebrew female slaves are essentially equal to the male Hebrew slaves. These women would serve for 6 years and then be liberated in the seventh year. Nothing in the text suggests that these women should wed their captors or that they should breed new slaves for their overlords.

The Time of Release

The text of Exodus is crystal clear; the male slave is released after six years of servitude. Deuteronomy, however, is somewhat ambiguous as it places the slave law after the law of the sabbatical. According to the sabbatical laws, there is a seven-year cycle for debts and loans; every seven years, all debts are abolished. Unlike the rule concerning the liberation of slaves, the period was not made running from the time of the individual loan, in order to form a kind of limitation of seven years. The seventh year was one for all debtors, even for those whose liability had been created a short while before. Extraordinary cancellation of debts was introduced by various Babylonian rulers, so this type of law would be something we should see in the these law codes when we see that these texts were influenced by their culture. 4

Thus, when Deuteronomy claims that the slave should be released on the seventh year, it may expect for them to be liberated on the sabbatical year, not after seven years of service. This makes sense only in Deuteronomy, which views the sabbatical year as a return to previous states, similar to the jubilee law in Leviticus 25. Exodus has no comparable law.

Where the Slave is Marked

According to Exodus, the slave who wants to stay beyond six years is brought “to God” which most likely refers to a local altar or shrine. The Elohist text of Exodus never places an insistence on centrality of worship as found in Deuteronomy 12, but if we read Exodus 20:24 it teaches regarding the construction of sacred altars “in all places where I record my name I will come unto thee, and I will bless thee.” For this reason, the author of Exodus 21 assumes the slave can approach one of many altars throughout Israel to have the marking performed, as there are several in this time period of Israel’s development (921-721 B.C.). This Elohist text of Exodus 21 is in variance with the same ritual as described in Deuteronomy 15:17, where the act is simply performed at the door, most likely at the house of the master. The reason for this distinction is that according to the Deuteronomist, there is only one place where God has chosen to place his name. This centralization of worship that is detailed in Deuteronomy 12 is a later theological modification of the Deuteronomist of the 7th century B.C. most likely put in place by Josiah (640-609 B.C.) or his priests. By recognizing that these textual traditions were put in place in completely different time periods, under very different circumstances, modern readers can understand these laws and see the Bible for what it is.

Explaining the Differences

Both of these slaves laws in Exodus and Deuteronomy have too much in common to not have influenced each other, and scholars closely following the Documentary Hypothesis see the Deuteronomist taking the Elohist text of Exodus 21 and reproducing it in a new way to fit the times and situation that they were facing in 640 B.C. This repackaging of this law is an illustration of the Documentary Hypothesis at work in a simple way that can be seen by the average reader of the Bible. By viewing these texts through the lense of the Documentary Hypothesis, the differences in these slave laws make more sense and their variances can be explained and understood.

The Deuteronomist had views that were different from the Elohist who wrote hundreds of years before him. This repackaging of this material helped the Deuteronomist to have scripture that was relevant and applicable in his day. Thus instead of a Hebrew slave that the master will liberate, we have a Hebrew brother, working for you, that is emancipated and compensated upon release, supposedly so that he will not find himself shortly thereafter in the same circumstance that made him a slave in the first place. This must be done because God, who blessed the slave owner and delivered the Israelites from Egyptian bondage must be remembered, one of the important motifs contained in the book of Deuteronomy.

In addition to this information, there is also evidence to suggest that the Deuteronomist worked to improve the plight of women. By abolishing the law of Exodus 21:7-11, where a father turns his daughter into a product to be bought and sold, the Deuteronomist effectively improved the lives of female slaves with a stroke of his pen, thereby putting them on equal footing with their male counterparts. 5

Finally, since Deuteronomy insists on centralization of worship (Deuteronomy 12), it would have been too difficult to take the slave who wanted to stay in the home of his master all the way to Jerusalem simply to pierce his ear, so what in Exodus was a religious ritual practiced at an altar or temple, becomes through the changes made by the Deuteronomist a secular rite that takes place in the home of the master.

The Priestly Text as found in Leviticus 25

39 And if thy brother that dwelleth by thee be waxen poor, and be sold unto thee; thou shalt not compel him to serve as a bondservant: 40 But as an hired servant, and as a sojourner, he shall be with thee, and shall serve thee unto the year of jubilee: 41 And then shall he depart from thee, both he and his children with him, and shall return unto his own family, and unto the possession of his fathers shall he return. 42 For they are my servants, which I brought forth out of the land of Egypt: they shall not be sold as bondmen. 43 Thou shalt not rule over him with rigour; but shalt fear thy God. 44 Both thy bondmen, and thy bondmaids, which thou shalt have, shall be of the heathen that are round about you; of them shall ye buy bondmen and bondmaids. 45 Moreover of the children of the strangers that do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy, and of their families that are with you, which they begat in your land: and they shall be your possession.46 And ye shall take them as an inheritance for your children after you, to inherit them for a possession; they shall be your bondmen for ever: but over your brethren the children of Israel, ye shall not rule one over another with rigour. 47 And if a sojourner or stranger wax rich by thee, and thy brother that dwelleth by him wax poor, and sell himself unto the stranger or sojourner by thee, or to the stock of the stranger’s family:48 After that he is sold he may be redeemed again; one of his brethren may redeem him:49 Either his uncle, or his uncle’s son, may redeem him, or any that is nigh of kin unto him of his family may redeem him; or if he be able, he may redeem himself.50 And he shall reckon with him that bought him from the year that he was sold to him unto the year of jubilee: and the price of his sale shall be according unto the number of years, according to the time of an hired servant shall it be with him.51 If there be yet many years behind, according unto them he shall give again the price of his redemption out of the money that he was bought for.52 And if there remain but few years unto the year of jubilee, then he shall count with him, and according unto his years shall he give him again the price of his redemption.53 And as a yearly hired servant shall he be with him: and the other shall not rule with rigour over him in thy sight.54 And if he be not redeemed in these years, then he shall go out in the year of jubilee, both he, and his children with him.55 For unto me the children of Israel are servants; they are my servants whom I brought forth out of the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.

The Priestly text, the last of the three textual traditions, stresses the importance of not placing the Israelite into slavery:

-

-

- You may not treat your brother like a slave (Leviticus 25:39).

- Your brother must be treated like a hired laborer (Leviticus 25:40).

- Your brother, and his family, returns to his ancestral land on the Jubilee year (Leviticus 25:41).

- God rescued the Israelites from Egyptian bondage, so they cannot be slaves (Leviticus 25:42).

- Do not abuse them as you must fear God (Leviticus 25:43).

- You may own perpetual male and female slaves, but they must be non-Israelites (Leviticus 44-46).

-

These different treatments for the Hebrew servant, the avoidance of the term slave (‘ebed), and the textual rationale for why an Israelite cannot be a slave to another Israelite—because they are servants of God and cannot be sold into slavery since they are Jehovah’s (Leviticus 25:42, 55)—together seem to make a persuasive argument against the older institution of Hebrew slavery. Through these editorial changes by the later Priestly author, the enslavement of Hebrews is prohibited by God.

There is another side to the Priestly author’s position regarding slavery as well. Hebrews are permitted to own slaves that come from the non-Israelite populations of their neighbors in this text. It is noteworthy that in these cases the slave is treated as property that can even be passed down to the next generation (Leviticus 25:46). So regardless whether the Pentateuch allows for Hebrews to be owned as slaves (Exodus 21:2-4; Deuteronomy 12:15-18) or forbids it (Leviticus 25:39-43), all of its textual traditions seem to allow the Hebrew to terminate his slavery or servitude if so desired after a specific time period: by the seventh year or the next jubilee year.

Exodus, Deuteronomy and Leviticus

As illustrated in this paper, the slave law in Deuteronomy is likely a modification to the law in Exodus. Leviticus is less similar to Exodus than Deuteronomy, with Leviticus and Exodus sharing few commonalities. Although in many basic areas the slave law in Leviticus varies from Deuteronomy, the two share definite features.

Both Leviticus and Deuteronomy avoid using the term ebed עבד for the servant, preferring to refer to the man as ‘ach אָח (your brother, or kinsman.)

Both Deuteronomy and Leviticus refer to the Israelite servant as akin to a hired laborer. Thus, although Leviticus has not rewritten the Deuteronomist’s slave law in the same way that Deuteronomy has rewritten the Exodus law, it appears as if the slave law in Deuteronomy has had some kind of influence on the author of Leviticus.

Conclusion

In contrast to the Deuteronomic law collection (Deuteronomy 12-26) and the Holiness Collection (Leviticus 17-23), the Covenant Code in Exodus, while coming to us from the Elohist, is part of a larger text known today as Exodus. Exodus is unlike Deuteronomy or Leviticus as it is a combination of different texts: E, J, and P, while the other two law collections have clear characteristics identifying their author. 6 The Deuteronomic Collection forms the core of the book of Deuteronomy (D) and reflects this scribal school’s philosophy, incorporating such ideas as the significance of the exodus and the standing of the lower classes, the text in Leviticus is part of the Holiness Collection of the Priestly author (P), and reflects the Priestly thinking of the Holiness school.

Although the slavery laws in Exodus, Deuteronomy and Leviticus may not represent the same situations, the differences between them clearly show modern readers that these texts come from different times and places, reflecting divergent notions of slavery. Exodus is the cruelest version, and Deuteronomy, with its more compassionate view, improves the lot of the Israelite slave. This merciful trajectory is continued in Leviticus, which just about abolishes slavery, turning slaves into indentured servants, but extending their period of subservience.

The differences between the arrangements of the slave laws in the different collections offer strong support for some kind of source criticism. All three laws disagree in substantial ways, such as whether the slave should be paid upon release and when the slave must be released. This latter, fundamental difference suggests that these divergent laws reflect various rules from different times and places. Once a student is subjected to the ideas surrounding the Documentary Hypothesis, it becomes easier to see in this case how the later laws were, in varying degrees, influenced by earlier ones which they then altered for their day.

I find it significant that the laws dealing with slavery have not been composed in a single location, and portrayed as cases and sub-cases, as we might expect in a text from one author. Instead, they are presented in three different places, and present their laws based on different conceptions of slavery. Similar differences between the Covenant Code (Exodus), the Deuteronomic Law Collection, and the Holiness Collection (Priestly text) are abundant in the Pentateuch, which I will write about in future posts.

The Documentary Hypothesis helps students of the Old Testament to see that these three diverse law collections come from different authors in various times and places. The Documentary Hypothesis will continue to be an important tool for students of the Bible as they work to understand these texts and how they are incorporated into the Old Testament.

Notes

-

-

- Isaac Mendelsohn, Slavery in the Ancient Near East (New York: Oxford University Press, 1949); Isaac Mendelsohn, “On Slavery in Alalah,” Israel Exploration Journal 5 (1955): 65-72.

- David Wright postulates that the Covenant Code (Exodus 21:1-23:19) was written sometime between 740 and 640 B.C. and that it drew its material from the Laws of Hammurabi. He writes, “The evidence indicates that the Covenant Code is a creative academic work, by and large a unitary composition, whose goal is mainly ideological, to stand as a symbolic counterstatement to the Assyrian hegemony prevailing at the time of its composition.” See David P. Wright, Inventing God’s Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 346.

- While there are many scholars that claim that the Priestly text is the last of the strains of the Pentateuch to be written, I do not believe that this is completely correct or that there is no evidence to go against this claim. Evidence exists which show that D was aware of P and was using these texts. See Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy and Deuteronomic School, Eisenbrauns, 1972, p. 179-189. He writes, “The redaction of the book of Joshua similarly points to P’s preceding D. As it was the Deuteronomist who gave the book its frame (ch. 1 = introduction, ch. 23 = conclusion) we may infer that the Priestly material was redacted by the deuteronomic editor and consequently antedated D… the fact that we meet with Priestly material in D and Dtr rather than the converse clearly demonstrates that the deuteronomic school was familiar with Priestly composition, while the Priestly school was not acquainted with D at the time of P’s recension. Not only does the deuteronomic school appear to have been familiar with the Priestly document, but sources which the Deuteronomist incorporated in his work also appear to have made use of Priestly material. Thus the annalistic passage in 2 Kgs. 16:10-16, for example, is written entirely in the Priestly idiom and is pervaded with ritual expressions encountered only in P, e.g. the combination of: burnt offering, cereal offering, and drink offering, throwing blood upon the altar… which was before the Lord, the north side of the altar (cf. Lev. 1:11), the morning burnt offering, model, pattern, and the like. The Priestly account treating of cult and temple affairs thus lay before the deuteronomic editor and must therefore date from an earlier time. The same is true of a similar annalistic passage in 2 Kgs. 12:5-17, which also pertains to temple affairs (the repair of the temple) and also contains many Priestly terms, such as: the money for which each man is assesed (v. 5; cf. Lev. 27), guilt offering, sin offering, (v. 17).

- Compare the law described by Fritz R. Kraus, Ein Edikt des Königs Ammi Saduqa (Leiden: Brill, 1958); Robert North, Sociology of the Biblical Jubilee, and de Vaux, Ancient Israel, 254.

- Claude Mariottini, Old Testament’s Deuteronomy puts women on equal footing, May 13, 2014, accessed 12.10.18.

- Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School, Eisenbrauns, 1972, p. 179 states, “In Pentateuchal literature we meet with two schools of crystallized theological thought: that found in the Priestly strand and that reflected in Deuteronomy. These two schools were, to be sure, antedated by the Jahwist and the Elohist documents. But J and E are merely narrative sources in which no uniform outlook and concreted ideology can as yet be discerned, and thus contrast strongly with P and Deuteronomic literature, each of which embodies a complex and consistent theology which we may search for in vain in the earlier sources.”

-

Further reading

Slavery in the Bible by Benjamin Scolnic

Slavery laws in the Old Testament by RationalChristianity.net

Slaves were commanded to be good slaves in the Bible? by Mike Day

The story of Joseph sold into Egypt – The Documentary Hypothesis in Effect by Mike Day

The Bible and Slavery – Wikipedia

What about the Bible and Slavery? by Wayne Jackson

No Comments

Comments are closed.